Barcelona's long urbanist saga to becoming a pedestrian paradise

Barcelona hasn't stopped evolving yet. With major pedestrianization projects underway, the Catalonian city is making its case to become the most walkable city in the world.

The invention and mass adoption of the personal vehicle left Barcelona with loud streets, poor air quality, and cars everywhere, but that’s all changing. An ambitious new plan is in action to expand its infamous ‘Superblocks’ (car-free pedestrian areas) throughout large parts of the city. This project came to my attention about a year ago as I was searching for grad schools to apply to.

Well, I found one.

To my surprise, I was accepted into the Barcelona School of Economics to pursue a Master’s degree in climate and energy economics. I chose this school for a lot of reasons - the coursework is climate-specific, the professors are world-class, and Barcelona has everything I’m looking for in a year abroad: tapas, vino, opportunities to practice my Spanish, and a massive pedestrianization project that I want to witness.

While I will certainly miss Albuquerque for the year that I’m away, I plan to continue Complex Effects and offer insight into Barcelona urbanism and culture. I’m excited to study climate economics in a city that is at the forefront of sustainable urban planning, and has a history of smart urban development.

Today’s post is a quick run-down on Barcelona’s storied path, and how good urban planning has proven prosperous for it before.

The details about the original founding of Barcelona are debated, but some ruins in the area date back earlier than 5,000 BC. The Romans were the ones who built the first area that resembled a city, and they made their mark about 15 BC. For hundreds of years, Barcelona experienced pretty slow growth amidst wars, takeovers, medieval protection plans, and so much more.

The map above shows the oldest, original, part of the city, the Gothic Quarter, which was confined within a wall - the result is a densely populated urban area with random, winding streets in the heart of the city. For most of the last two centuries, Barcelona looked something like this.

While the density and mixed-use nature of the Gothic Quarter is great for tourists today, living conditions for Barcelona’s residents by the early 1800s were low. As the population rose, the increasing density within the city walls led to disease, filth, and general displeasure. Eventually, due to these issues and geopolitical changes, the walls were destroyed and the city made plans to expand outside the city walls.

The Eixample (expansion) grid pattern was recommended by city planner, engineer, and city councilor, Ilefons Cerdà as a way for Barcelona to grow in a flexible, sustainable way. Cerdà, now regarded by many as one of the most forward-thinking urban planners of all time, imagined a grid pattern of buildings 113m x 113m, with blunted corners, and streets that connected Barcelona with the nearby villages.

Cerdà ran surveys and studied inequality, local living conditions, urban sanitation, optimal street width for airflow, underground trains, and more, and devised a plan to tackle all of these issues:

The buildings were designed to promote health, equality, and social space - the configurations of which would vary by use, and provide light and airflow:

Each angle, negative space, and detail was considered by Cerdà. Zergat Institute of Technology notes:

To understand its peculiar geometry a little better, we can see how Cerdà conceived two basic shapes in the spaces of each block to locate the buildings. One had two parallel blocks located on opposite sides, leaving a large rectangular space inside for garden areas, while the other had two blocks joined in an "L" shape, leaving a large square space in the rest of the block also for gardens.

As time passed, of course, political pressures and a changing economy meant Cerdà’s plan would change many times over. Cerdà never saw his vision come to fruition.

Instead of limiting each block to 2 or 3 buildings to allow for public space, light exposure, and high air quality, most blocks were fully built out on all sides, height restrictions were loosened, and parking garages were constructed in the block centers. At the turn of the 20th century, the personal vehicle swept over Europe and Barcelona became riddled with cars. The city, for a long time, was noisy and had some of the worst air quality in Europe.

Zergat Institute of Technology notes:

It was not until 1950 that the city's extensive tram network began to experience a series of urban planning problems directly related to population growth. Due to the growing demographic waves towards the metropolitan area, the original tram network was progressively replaced by the presence of the private car, the new buses and, in general, the automobile boom. In 1971, the old tram network disappeared for good. Today, the only legacy that allows us to go back to that time is the Tramvia Blau...

While Cerdà’s ultimate vision did not come to fruition, the flexible foundation of his plan is still present. The Eixample is again being put to the test in a way perhaps not even imagined by Cerdà - enter Salvador Rueda.

In 2016, the Barcelona city council tapped Salvador Rueda, a noted expert in the field of urbanism, to lead the effort to renew the urban space of Barcelona. Salvador found his urbanist utopian plan at the forefront of the city’s newest sustainability plan despite heavy opposition from the business community.

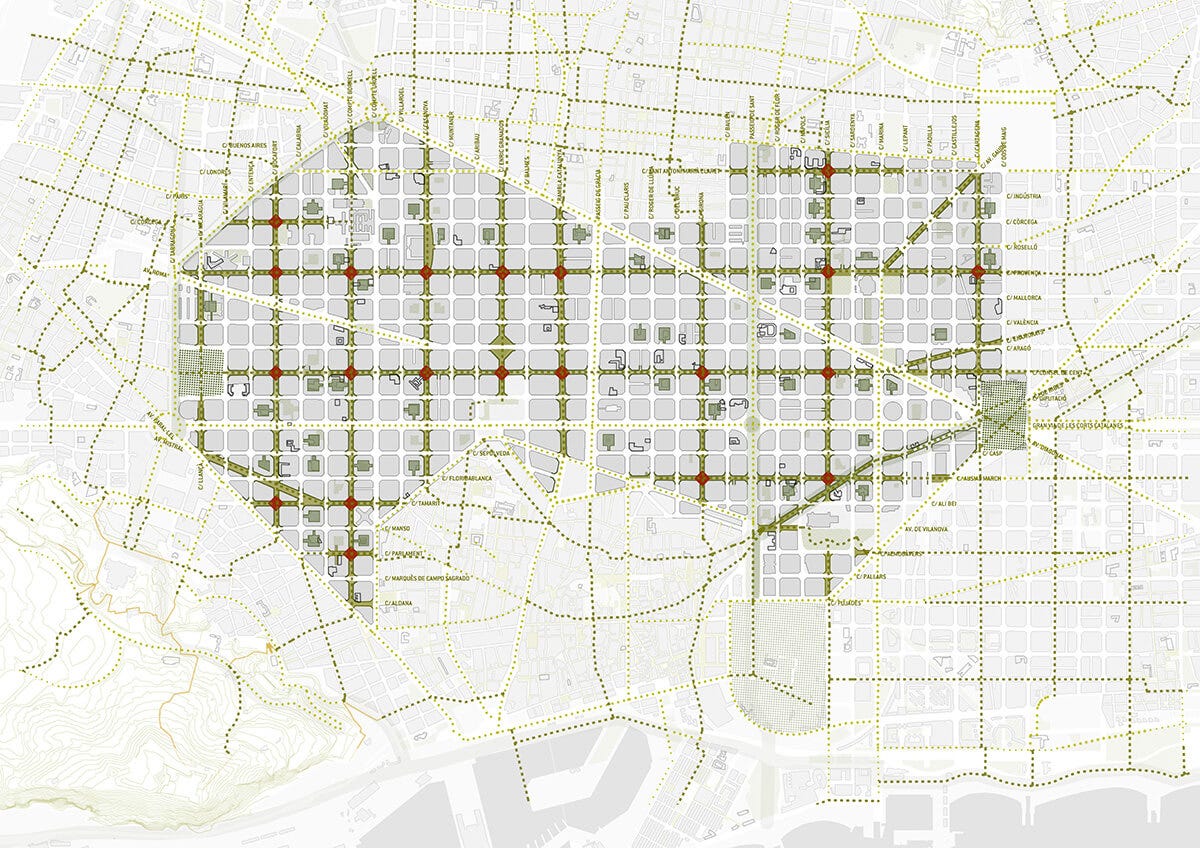

Rueda was determined to put Cerdà’s Eixample to use by creating the first ‘Superilla de l’Eixample’, or ‘Superblock’ - a 3x3 group of blocks where car traffic is nearly banned except for emergency and practical uses, and the roads are replaced with greenery, cycling paths, and pedestrians. Outside of the 3x3 superblock, cars are free to move as before:

The goal is to have all the amenities anyone needs day-to-day inside each 400m x 400m Superblock - grocery stores, entertainment, parks, schools, public gathering places, pubs, etc., and increasing greenery and public spaces, like Cerdà wanted, would promote biodiversity and social cohesion.

On top of all of those benefits, the city hoped the plan would be good for local businesses despite their opposition. Barcelona.de notes:

The superblocks are at the heart of a concept for sustainable mobility developed by the city administration in 2016. The first superblock was built in 2017 in the Poble Nou district - initially against opposition from business people and drivers, but with great approval from local residents. In the so far designed superblocks that have emerged throughout the city, the feared business death has not materialized. On the contrary: the number of local shops rose by as much as 30 percent.

Given the success of the initial Superblocks, Barcelona has since decided to double down on the pedestrianization project with plans to expand the idea throughout nearly the rest of the city core:

By 2024, Rueda and the city aim to have 81% of all travel in the city be by foot and look to completely revamp the public transit network to be faster and more efficient.

Within just the last few years, Barcelona has turned into a pedestrian paradise. While there is still much work to do, Rueda, unlike Cerdà, has been able to witness his vision come to life. Vox reports:

In his mind’s eye, [Rueda] sees a city no longer dominated by automobiles. Most streets once devoted to cars have been transformed into walkable, mixed-use public spaces, what he calls “superblocks,” where pedestrians, cyclists, and citizens mix in safety. Each resident has access to their own superblock and can traverse the city to visit the others without the need for, or fear of, motorized private vehicles.

The project is ambitious in scale, but the idea of giving the streets back to the people is nothing new. Cities like Paris, New York, Vienna, and Milan are following similar paths. It’s likely a path that most cities can follow.

Cities were not meant to sprawl and die from the inside out, they were meant to grow incrementally from the bottom up, constantly evolving to become better. And most importantly, cities are meant to plan ahead. Far ahead.

At the core of Barcelona’s plan is tactical urbanism - providing the city with a strong foundation to evolve continuously.

Tactical urbanism establishes long-term strategies and therefor requires tactical interventions to adapt the shortcomings of a conventional model, establishing tools and measures that can be applied quickly, reduce costs and, above all, propose temporary solutions to the problems detected. In this case, it proposes an alternative model to achieve urban regeneration that works mainly on a small scale. Moreover, as we have seen and are seeing, a tactical project can lead to positive changes in an entire neighbourhood.

From a small walled-in city to a futuristic pedestrian paradise, the story of Barcelona’s urban development is easy to get lost in. And I’m guessing it’s far from over. I’m excited to watch Rueda’s Superblock plans continue next year - likely from a walkable street serving tapas as I read an energy textbook.