Rural New Mexico has some challenges ahead

Population trends paint a scary picture for local and state tax revenues

New Mexico’s population has been nearly stagnant since 2010. I recently wrote about this issue and how policymakers should respond by focusing on housing abundance, attracting immigrants from Central and South America, and promoting remote work. While it may seem like a trivial problem, a dwindling population could lead to less societal investment from public and private entities.

In New Mexico’s public realm, governments and school districts rely on gross receipts taxes (GRT), gas taxes, and property taxes in order to finance improvements in utilities, roads, kindergartens, public safety, hospitals, and much more. Therefore, population and tax trends can tell you a lot about which regions of New Mexico may need extra attention from policymakers.

In the private realm, companies want to see that there are enough workers and infrastructure to support their ventures. If a city can’t attract or retain jobs, it loses tax income to finance infrastructure and schools - a vicious cycle of poverty that New Mexico knows all too well.

Today’s post is about the population trends I have been paying attention to in New Mexico. Urbanization and climate change will tell the story of New Mexico’s population changes over the next 50 years. Rural areas, and the state in general, will have to get creative to overcome these challenges - let’s dive in.

The population of New Mexico could start trending down

Throughout the 1900s, all Western states seemed to benefit from migration and growth. During this time, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Arizona all saw very similar growth, but something changed in 2010. A culmination of birth rates dropping, immigration slowing, and college graduates moving away in greater numbers led to the past 13 years of stagnation. While there has been minor growth since 2010, the growth has been below the national average and well below the growth of New Mexico’s immediate neighbors: Colorado, Arizona, Utah, and Texas:

This is troubling for many reasons, but in a nutshell, population decline could mean, among other things, decreased tax base and infrastructure investment, and therefore increased poverty and crime.

A report by New Mexico’s Legislative Finance Committee (LFC) reported the following on the issue in 2021:

Between 2010 and 2019, New Mexico’s birth rate fell by 19 percent, and the under-18 population shrank by 8.3 percent. At the same time, the working-age population (18 to 64) declined 2 percent, and the over 65 population grew 38 percent. While the state’s non-Hispanic white population shrunk slightly and the Hispanic population grew slightly, the Native American population grew almost 10 percent from 2010 to 2019, signaling long-term growth in the state’s diversity. In about a decade, New Mexico is projected to start seeing overall declines in population. Projections indicate declines in younger ages and rural areas will continue and likely be exacerbated by Covid-19. Given the status quo, New Mexico is heading toward having more, older New Mexicans using relatively expensive public services (e.g. Medicaid and Medicare) and fewer, younger New Mexicans in school and working. While birth rates are continuing to fall, 43 percent of children who disenrolled from public schools during Covid-19 are moving out of the state, and the number of high school graduates is projected to decline 22 percent by 2037. The state should be intentional about right sizing capacity or examining alternative strategies to address these trends. For example, LFC reports have repeatedly documented the consequences of overbuilding pre-school capacity for 4-year-olds given the declining birth rate and has documented instances of lost federal dollars due to lack of coordination. Additionally, since 2016 public school enrollment declined at a rate of 3 percent a year and higher education declined at a rate of 5 percent a year. Meanwhile, the state’s working age population is shrinking due to net-outmigration.

I often hear New Mexicans talk about keeping our state a “secret” because they don’t want California-style traffic and housing prices, increased water usage, and more urban sprawl. While those concerns are warranted, we should realize that people are not the issue in this equation - it’s policy. These outcomes can easily be overcome with a more efficient and sustainable built environment, more sustainable water laws, and policies that aim for housing abundance. If you worry about things like public school investment, job growth, and infrastructure improvements, you should want more, not fewer people in New Mexico.

The population of New Mexico is the tax base that funds our schools, roads, outdoor recreation, large public-sector industry, and more. A dwindling tax base means New Mexico’s issues get worse, not better. This is also true on a local level.

Many small towns across the US are experiencing decreasing populations as people look for all the things big cities offer. In New Mexico, rural flight has the potential to be exacerbated by climate change and our need to shift away from fossil fuels.

Urbanization and decarbonization spell uncertainty for rural New Mexico

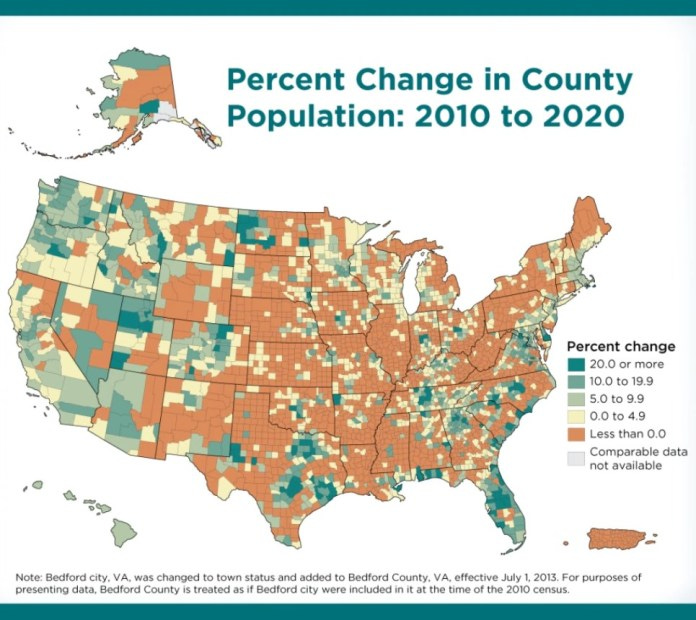

New Mexico is experiencing the same urbanization as the rest of the US (besides Idaho in 2020, I guess) - people are leaving rural areas and moving to bigger cities:

This rural flight has been happening for a while. Most rural counties saw negative growth since 2010, but the 2010s were mostly good for the Permian basin - the oil-producing area of Southeastern New Mexico and West Texas. New Mexico increased its oil production during the 2010s and became the second-highest oil-producing state in the US - boosting the populations of Lea, Eddy, and Otero Counties (Southeastern NM):

Lea is the Southeasternmost county in New Mexico - the heart of the Permian Basin where the local oil and gas industry props up the economy. If you look at GRT collections for Lea County below, you’ll see oil and gas extraction (in red) consists of over 1/3rd of their economy:

As you can imagine, all five Lea County Commissioners are Republican, and the county doesn’t seem to be in any hurry to decarbonize. Most of the major clean-energy projects in New Mexico are being announced elsewhere. Luckily, since marijuana was legalized in the state, Jal has diversified its economy a little with a few pretty successful dispensaries.

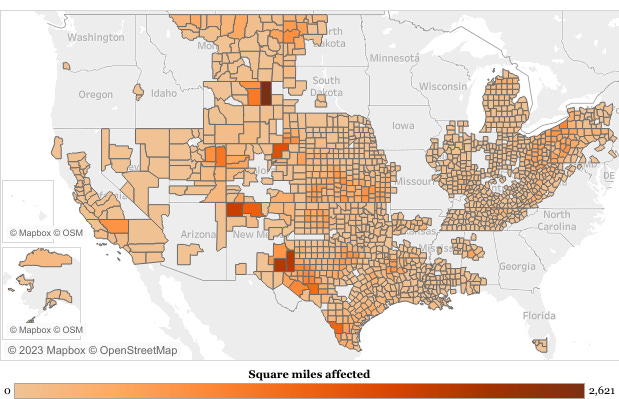

Side Note: The oil industry’s investment in Lea County has been good for the tax base, but poor for the air quality. According to a Tableau map created by Dan Schwartz of The Santa Fe New Mexican, “Methane pollution [in Lea County] affects 2,034 square miles of land… and 38.96% of the population, which is 25,220 people… there are 16,201 oil and gas facilities.”

Schwartz’s map shows the severity of the methane pollution in New Mexico’s oil-producing counties compared to the rest of the country:

Over the next few decades as New Mexico decarbonizes, people will be leaving oil-producing counties that don’t diversify their economies, tax revenues will decline, and they’ll have trouble paying for roads and schools.

It’s true that transitioning away from oil and gas is getting easier as renewables decrease in price, but how is the Permian basin going to respond to that? So far, the Permian basin has far more oil rigs than renewable energy projects:

At a local level, oil-producing counties and municipalities that don’t attract clean energy investments will lose jobs, and therefore people and tax revenue. At a state level, New Mexico might avoid major revenue decreases by instigating clean energy investment (which they are doing - mostly in central and northern New Mexico), and by preparing state budgets for revenue loss by using now-plentiful oil revenues to create permanent funds (which they have been doing), but we have yet to see if that will be enough.

Now, to be fair, not all of the population trends (from 2010 to 2020) are bad. Not only are all the larger cities growing - like Albuquerque (6.2%), Santa Fe (29.5%), Las Cruces (19.9%), and Los Lunas (24.3%), but many smaller, non-oil-producing, municipalities are growing as well - like Santa Teresa (27.4%), Thoreau (147.3%), Chaparral (22.2%), and Edgewood (68.5%).

We can look at these small towns that are flourishing without oil and gas extraction for guidance on navigating urbanization and decarbonization. Santa Teresa is leveraging its proximity to trade partners like Mexico and Texas to foster development, Edgewood attracts residents due to its rural feel and proximity to Albuquerque, and Corona is attracting clean energy jobs with its wind resources.

If the LFC projection is right, and New Mexico’s population starts declining in eight years, we won’t be able to say we didn’t see it coming. Lea County should tap into the plentiful Inflation Reduction Act funding before it’s all spoken for, Albuquerque should prepare for sustainable urbanization, and policymakers should realize our oil boom can’t last forever.