Leveraging Pueblo wisdom to overcome climate change

By responding to New Mexico's changing climate in the past, Native Americans have already discovered how to be resilient. Implementing ancient wisdom on diversity may be our ticket to net-zero.

In a great deal of various unrelated contexts, you will find that diversity outperforms homogeneity.

Let me explain by giving you some examples:

Over the long term, investors are better off purchasing index funds tied to an entire market, like the S&P 500, than betting on a single company’s stock.

Organizations with people from varying backgrounds, ethnicities, and cultures are statistically more likely to innovate.

In nature, biodiversity is essential to supporting life on Earth.

Multi-faceted, complimentary economies are stronger than economies that rely on any single industry to survive.

For more examples, I would recommend reading the book by David Epstein Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World.

Diversity is necessary for our survival as mere chimps in a complex world. Still, we often try to beat diversity with technological advancements, brute force, and speculation - often leading to a lack of resilience to changing environments. For example, investors will try to outsmart the market by betting on certain stocks - and they might make a lot of money in the short term, but even the greatest investors alive can’t beat the market long-term. Technology changes, unexpected disasters occur, climate changes, etc., - even Warren Buffet, over the last twenty years, has not outperformed the S&P 500.

In agriculture, farmers try to cut costs by planting monocultures of plant species that are easier to cultivate and treat with machinery. If the crops aren’t suited to the regional climate and environment, and don’t have a complimentary ecosystem around them, they might depend on pesticides, fertilizers, and unsustainable amounts of water to grow adequately. This has resulted in a food industry that isn’t prepared for climate change, has razor-thin margins (which drives out small farmers), and needs to evolve quickly - especially in semi-arid regions like New Mexico.

But what does the agricultural system need to evolve to?

Someday soon, New Mexico may have to grapple with the fact that agriculture accounts for about 75% of water usage. With extreme water scarcity looming in the next 100 years for New Mexico, our communities need to rethink how they utilize water. We may need several policy solutions similar to Gov. Lujan-Grisham’s ‘Strategic Water Supply’ idea, but maybe more importantly, we need to replace the water-intensive pecan and alfalfa crops with something more resilient to New Mexico’s current and future climate.

Native Americans have regionalized wisdom that we can use to combat climate change. The Native people of New Mexico have lived here for thousands of years, and have been molded by the land through adaptation and the passing down of ancient wisdom. Pueblo people in New Mexico have persisted through varying climatic conditions over thousands of years - because they have worked with the land and responded to nature’s variances.

One particular thread of native culture we can turn to for guidance is their agricultural practices. Like index-fund investors, Native Americans relied on the strength of cooperation and diversity to bear more fruit (literally).

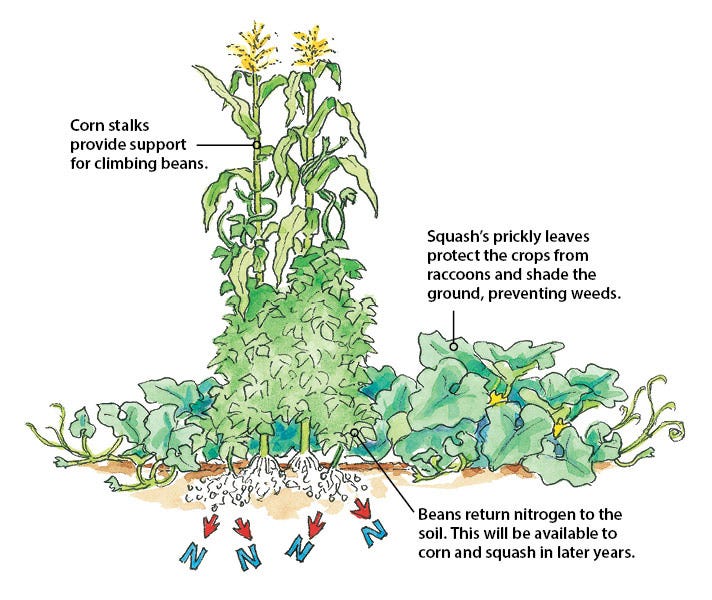

Beans, corn, and squash, each have physical and chemical qualities that help the other two overcome weaknesses - making them more productive planted together than apart. This trio is called ‘The Three Sisters.’

Albuquerque’s Indian Pueblo Cultural Center states:

From the Northeast to the Southeast, from the Plains to the Southwest and into Middle America, many Indigenous communities grow varieties of this trio… The name, the “Three Sisters,” comes from the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois). Different communities have stories; the common thread is that the three sisters are very close – stronger together than apart.

First, plant the corn. The stalks provide a pole for the beans to wrap themselves around and help to stabilize the corn in wind. Beans provide nitrogen to fertilize the soil. The large, spiny squash leaves provide shade, help the soil retain moisture, prevent weed growth, and discourages insects from invading. Each of the three attracts beneficial insects that prey on those that are destructive.

When eaten together, corn, beans and squash are a complete and balanced meal.

Now, I’m not an expert on agriculture or Pueblo culture, but I think there’s wisdom to be found in how Pueblo people found ways to survive, and even thrive, in New Mexico. Often regarded as a harsh climate that can’t sustain “too many people,” New Mexico’s climate is arguably misunderstood. I often hear climate doomers blame climate change on high populations of humans. Instead, I think it’s a lot more about how people live, rather than the amount of people there are.

Native Americans in New Mexico lived in rather large numbers without any real perceived carbon footprint. They lived in harmony with their environment and navigated the good and hard times.

Brandon Morgan, Ph.D. wrote:

When the first Europeans arrived in New Mexico, they found between seventy-five and eighty different towns that covered an area from the Piro villages of the middle Rio Grande to Taos in the north, and the Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi villages to the west and Cicuye (Pecos Pueblo) to the east…

The environment facilitated the growth of culture and artistic production during the Pueblo Golden Age. Rain was plentiful and climatic conditions contributed to prosperity and overall political stability. At the apex of the Golden Age, there may have been as many as 150 large Pueblos with between 150,000 and 250,000 inhabitants (estimates vary widely). Near the end of the era, during the 1520s, drought returned. Shortly thereafter, the Coronado expedition disrupted life in the region.

The end of the Pueblo Golden Age was not the first time the climate changed life in New Mexico. Morgan notes:

[In] 9,500 BCE, sweeping patterns of climate change transformed New Mexico and the surrounding region. It became much drier and hotter, more like the types of conditions that are present today. Human beings were forced to make difficult decisions about how to adapt to their altered surroundings. Most responded by hunting smaller game and gathering different types of plants for food. They also sought out sources of water, principally along the Rio Grande corridor, but also along other regional rivers, such as the Canadian, Colorado, Conchos, Gila, Pecos, Salt, and San Juan. Other factors, including rainfall, landscapes, altitude, and temperature, influenced the way people lived.

And of course, today, 500 years after the Pueblo Golden Age ended, shifts in the climate again threaten New Mexico. What can we do to prepare for it?

The answer just might lie in the wisdom of ‘The Three Sisters.’ Barcelona School of Economics researcher, Andre Groeger, while researching how rural communities grow wealthier and develop more complex economies, found that “farmers could be better off by diversifying agricultural activities.” Groeger says “Innovative rural development solutions that foster structural transformation will be critical for improving the livelihood of rural populations.”

Diversifying crops in a cooperative and regionally appropriate way could help New Mexican farmers increase production while using fewer resources like water - growing their local economy, and becoming more resilient to the changing climate. I know modern farmers are constantly looking to optimize and work around razor-thin margins, and I don’t pretend to know about everything farmers go through in New Mexico, but I know a larger structural change is needed to make sure the farmer’s business model is ready for a net-zero economy.

New Mexico needs to diversify its agricultural economy away from pecans and alfalfa to save water, produce more food, grow and diversify the economy, and optimize for climate change. We could spend a lot of money researching how to diversify our agricultural communities perfectly - like with optimized agrivoltaics, species pairing, etc. - but a simple way to start is to look to New Mexico’s first people and their wisdom on diversity, place, and connection.

The Three Sisters and the regionalized wisdom of Native Americans should be taken more seriously. As Epstein argues in Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized, humans tend to learn and innovate via analogies. By taking knowledge from seemingly unrelated contexts, like index-fund investing or The Three Sisters, maybe we can rethink how our local, regional, and global economies are supposed to work.

One of the ways that pueblo people have come to understand who we are in this world, not only from a modern perspective, but from a historical lens too, is that place matters. We are people of place names. Everything connected. Everything is related with regard to people, animals, plants, sky, water, rocks, and we also believe that we come from the land. And there’s places that we can actually point to of emergence, and that is really significant when we think about our larger connections to how we come to be in this world…

- Matthew Martinez, Ph.D

I adamatly agree with you. There are many ways we can prepare for the future and recognizing the value of the New Mexico Native American culture is one way to ensure that we can continue to thrive in New Mexico's arid region with the water resources available. Thank you for writing this informative piece.