Marching through history with Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta led meaningful change for millions of workers with the late Cesar Chavez, and she led us through the Barelas neighborhood last Saturday.

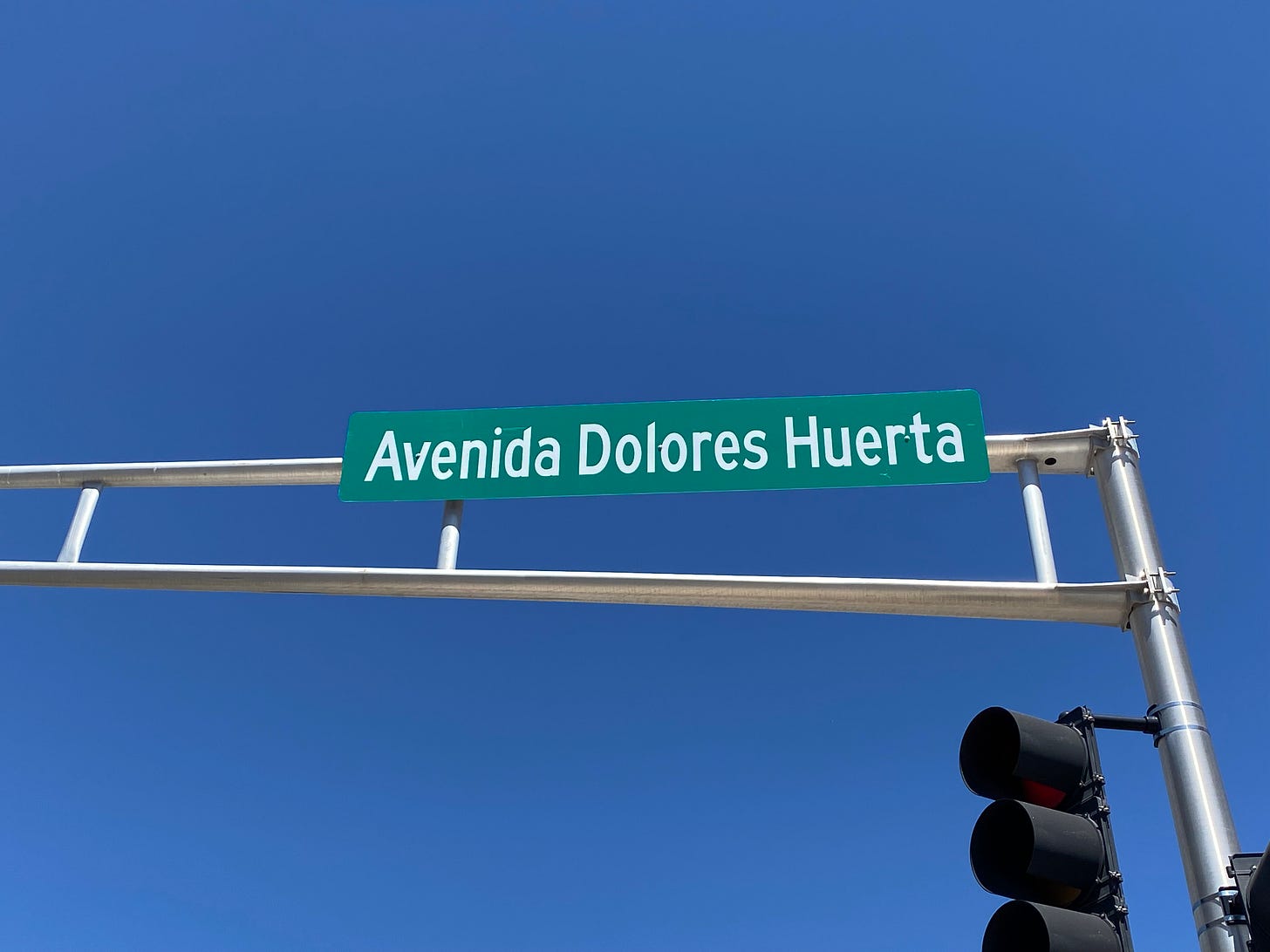

Avenida Dolores Huerta runs through the 500-year-old Hispanic neighborhood of Barelas in Albuquerque, NM. Just South of the street, adjacent to the Rio Grande, is the one and only National Hispanic Cultural Center (NHCC).

The NHCC is where the festivities began honoring Dolores Huerta and the late Cesar Chavez on April 13th, 2024. Dolores, one of the most influential labor activists of the 20th century, blessed the event with her presence this year - seeming to increase the energy of the crowd beginning to form on the leafy NHCC campus.

The NHCC has been hosting the Annual César Chávez And Dolores Huerta Celebration - the only celebration of its kind according to the NHCC, since 2007.

The celebration started with a good old-fashioned march through the Barelas neighborhood. There were hundreds of people in attendance. As the various organizations prepared for the march, there were traditional Native American dances, low riders sliding through the parking lot all low to the ground, and everything New Mexican in between.

The golf cart carrying Dolores Huerta, Mayor Tim Keller, State Treasurer Laura Montoya, and other important people led the march from the NHCC parking lot going North on 4th Street. My girlfriend and I tucked in behind the Carpenters Union and followed Dolores toward Downtown

As we crossed Avenida Cesar Chavez (where the road becomes Avenida Dolores Huerta), the “si, se puede” chants started fading in and out for the next hour or so.

I have walked this stretch of 4th street through Barelas plenty of times before, but it had never had the charm it did on the morning of Saturday, April 13th. In the center of the road, I had a better view of the buildings on either side. 4th Street was at one point Route 66 before it was redirected to Central and has garnered newer developments like the NHCC and the soon-coming Barelas Central Kitchen, but the street is mostly lined with some of the oldest buildings in the city - mostly vacant.

As Dolores led us through Barelas, murals and empty stores lined the streets of the inner-city neighborhood.

Dolores was born in Dawson, New Mexico in 1930. Her father Juan Hernandez, also born in Dawson, was the son of immigrants and worked in the local coal mine. He later joined the migrant labor force working at beet farms around the US and became a New Mexico State legislator in 1938. When Dolores was 3, her parents divorced and her mother moved her and her two brothers to Stockton, California.

Her father had stayed in Dawson after the divorce, and she didn’t speak with him much after she left New Mexico. In Stockton, her mother bought and ran a 70-room boarding house for farm laborers - often letting many of them stay for free in hard times. From Dawson to Stockton, Dolores witnessed underpaid immigrants working the mines and grape fields. Today, she credits learning her activist ways from her mother.

After high school, Huerta attended San Joaquin Delta Community College where she received her teaching credentials - uncommon for a Mexican American woman at the time. While teaching, she noticed many farmworkers’ children coming to school hungry.

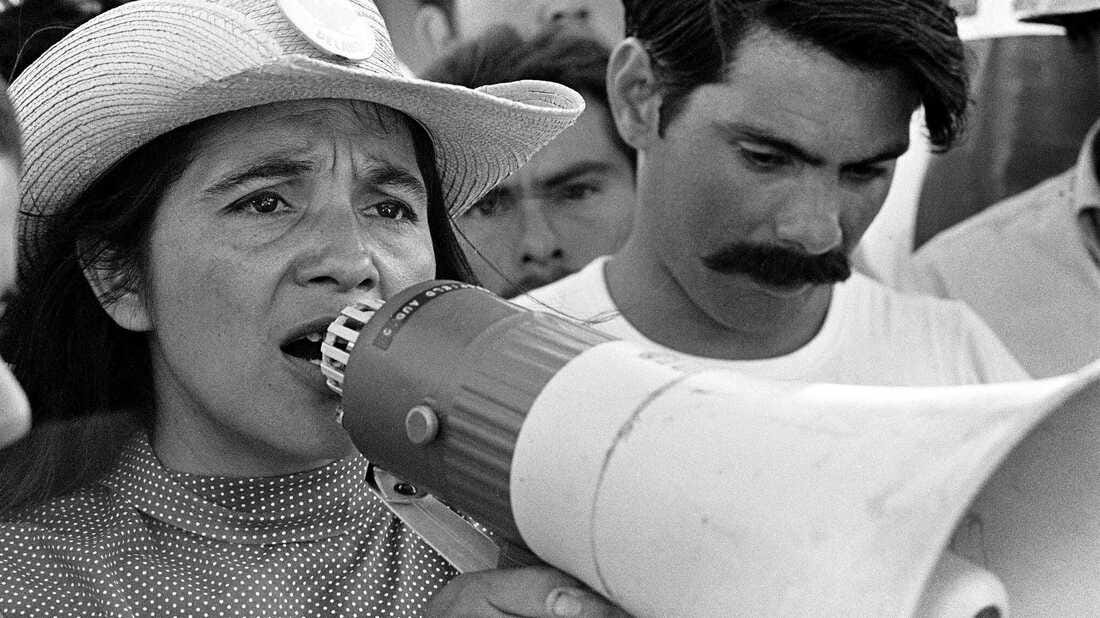

Dolores told NPR:

The farmworkers were only earning about 70 cents an hour at that time — 90 cents was the highest wage that they were earning. They didn't have toilets in the fields, they didn't have cold drinking water. They didn't have rest periods. People worked from sunup to sundown. It was really atrocious. And families were so poor. I think that's one of the things that really infuriated me. When I saw people in their homes — they had dirt floors. And the furniture was orange crates and cardboard boxes. People were so incredibly poor and they were working so hard. And the children were [suffering from malnutrition] and very ill-clothed and ill-fed.

Dolores taught for a while and then decided she could help her students more if she organized farmers and farm workers. Like a relay - she picked up where her activist mother had left off.

NPR writes:

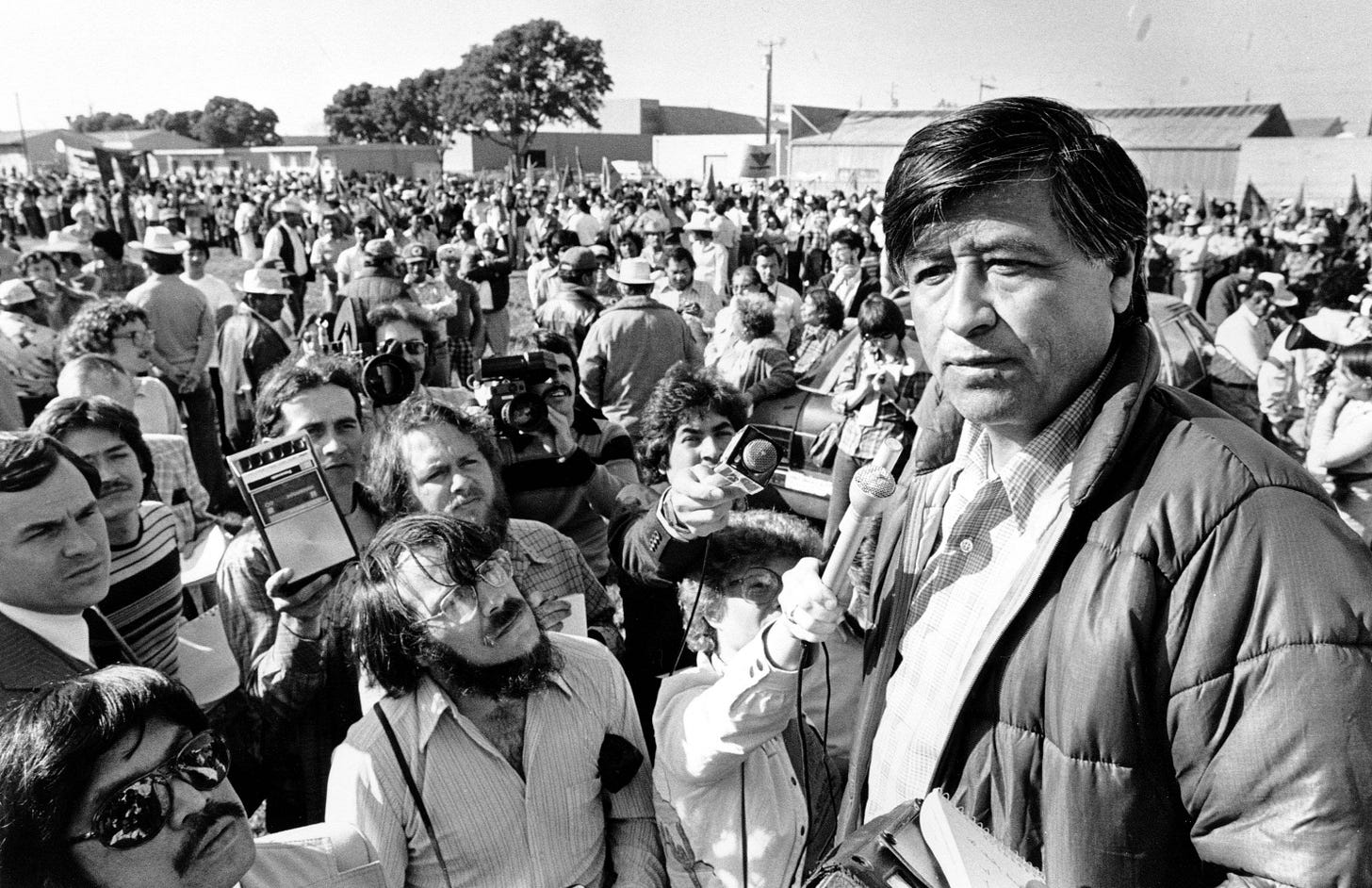

Huerta was 25 when she became the political director of the Community Service Organization, run by influential community organizer Fred Ross. That's where she met Chavez, and in 1962 the two teamed up to form what became the [United Farm Workers (UFW)], organizing farmworkers who toiled for wages as low as 70 cents an hour, in brutal conditions.

"They didn't have toilets in the fields, they didn't have cold drinking water. They didn't have rest periods...”

Huerta would coin the phrase ‘Si, se puede,’ giving the United Farm Workers its legendary catchphrase. While Huerta and Chavez shared leadership of the UFA, Chavez was the spokesperson of the organization - often leading to him getting more credit than Huerta throughout the years.

Leading countless marches and protests, Huerta faced violence and prejudices on the picket line - once obtaining broken ribs from the force of a policeman’s baton.

As the Downtown buildings got closer, the crowd went through waves of ‘Si, se puede’ chants, and other chants denouncing tax fraud, inequality, etc.

Dolores’ cart turned the march East on Iron Street through a more residential part of Barelas. Residents observed the crowd from their front doorways as our chants broke the silence of the quiet Saturday morning. We turned South on 8th Street where Albuquerque’s Spring views and temperature didn’t disappoint.

Barelas is the oldest neighborhood in Albuquerque, predating the city itself, and was born out of an old agricultural community at the intersection of El Camino Real and the Rio Grande. The community has seen great change over the last 500 years. As agriculture, railroad companies, and Route 66 all came and went - leaving boom and bust cycles for the now inner-city neighborhood - the neighborhood feels yet again on the brink of change.

New development is bringing life into the vacant 4th Street and Rail Yards while the city and residents wrestle with the prospects of gentrification.

We marched down 8th Street back to the NHCC campus to kick off the rest of the celebrations for Huerta and Chavez.

The New Mexican culture was palpable at the NHCC. We ate frito pie, listened to mariachis, and shouted “Que viva!” whenever necessary.

Speeches by the NHCC President, Albuquerque Mayor Tim Keller, and others all praised Dolores and the meaningful change she helped bring to people in New Mexico and around the US.

Mayor Keller, in his speech, announced that the City of Albuquerque and the State of New Mexico officially recognized April 13th as Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez Day - an honor recognized in states and cities across the US. Keller went on to talk about recent local achievements activists have garnered for New Mexicans like free college education, child care, and daycare - and there’s no doubt these achievements were only possible because of the foundation of rights Huerta helped establish during the labor movement.

Dolores, now 94 years old, spent most of her life marching through streets across America - achieving improved working conditions and wages for millions of migrant workers and farmers across the United States.

Today, union membership across the US is again on the rise, thanks to the efforts of new grassroots organizers across the US. But much like the future of Barelas, the future of the revived labor rights effort is yet to be determined.

New buildings will be erected, new activists will emerge, and vacancies will need to be filled, but the relay continues. Filling the shoes of Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez is no easy task, but last Saturday, I witnessed hundreds of young activists marching through the streets of Barelas inspired by Dolores’ run - hopefully ready to pick up the baton next.

Si, se puede!