New Mexico's Lost Decade

After the Great Recession, New Mexico endured years of stagnation and stubborn poverty while nearby states rebounded. But new economic shifts could mark a turning point.

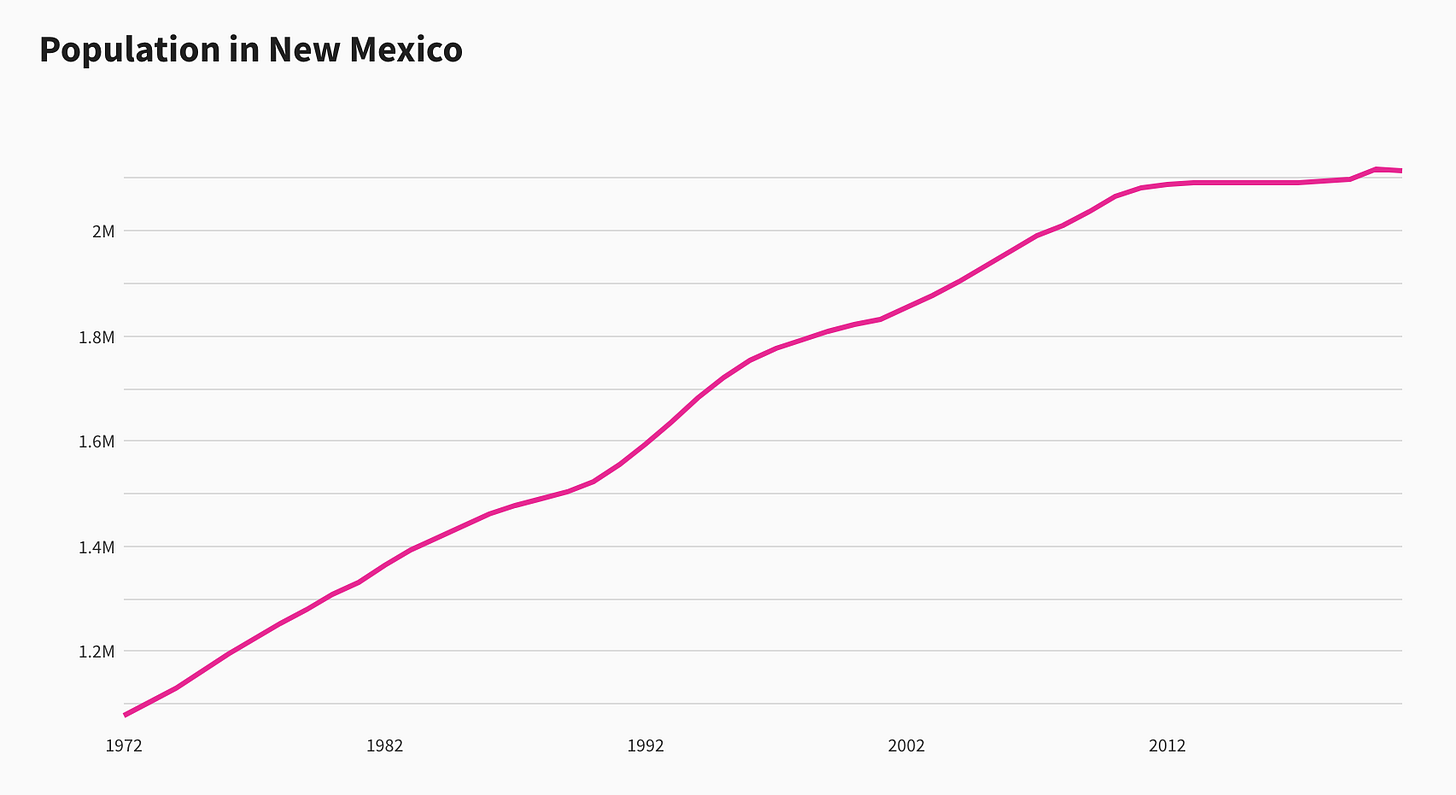

New Mexico’s “Lost Decade” starts at the 2008 Great Recession and ends, economists say, somewhere around 2019. It’s highlighted by stagnant population growth, rural flight, lost jobs, and an economic landscape in flux. Some regions fell out of prominence while others rose from the desert, and in the end, I argue, New Mexico has been left with scars, but also an opportunity.

I plan for this to be a two-part series. First, we’ll go over New Mexico’s lost decade. And in a later post I’ll write about New Mexico’s opportunity to turn the page on the lost decade and become an economic development powerhouse. So for now, let’s go back in time to the start of the lost decade - back to 2008.

The Shock

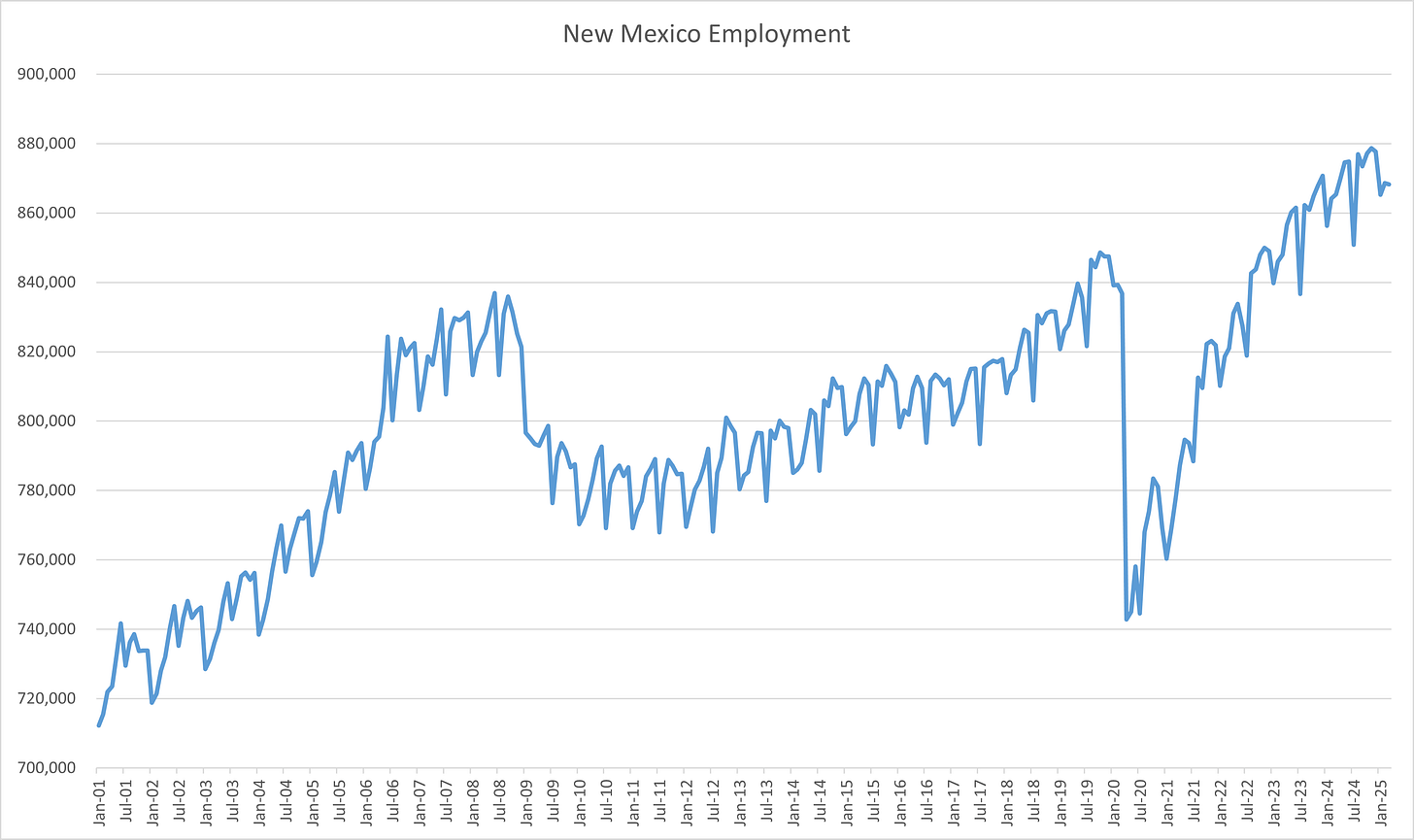

The 2008 financial crisis, also known as the global financial crisis (GFC), exacerbated the Great Recession. I’m going to use these terms interchangeably throughout this post to describe the time in which New Mexico’s lost decade started. The cause of the crisis included excessive speculation on property values, which led to a pile of defaulted mortgages, a liquidity crisis, the collapse of Lehman Brothers, bank runs, and a stock market crash. Unemployment spiked around the country, and while New Mexico has always had high poverty rates, it was exacerbated for about a decade.

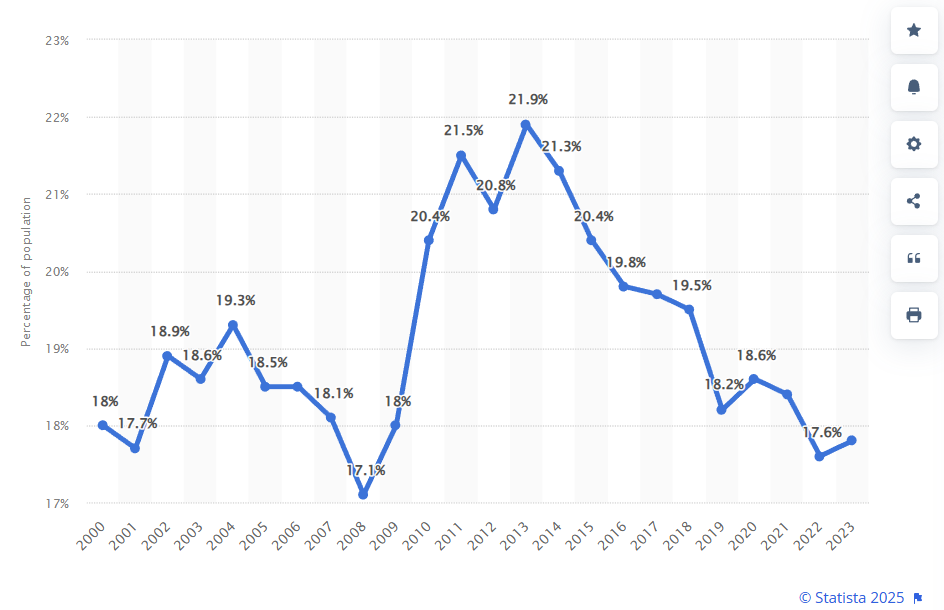

Poverty rate in New Mexico from 2000 to 2023

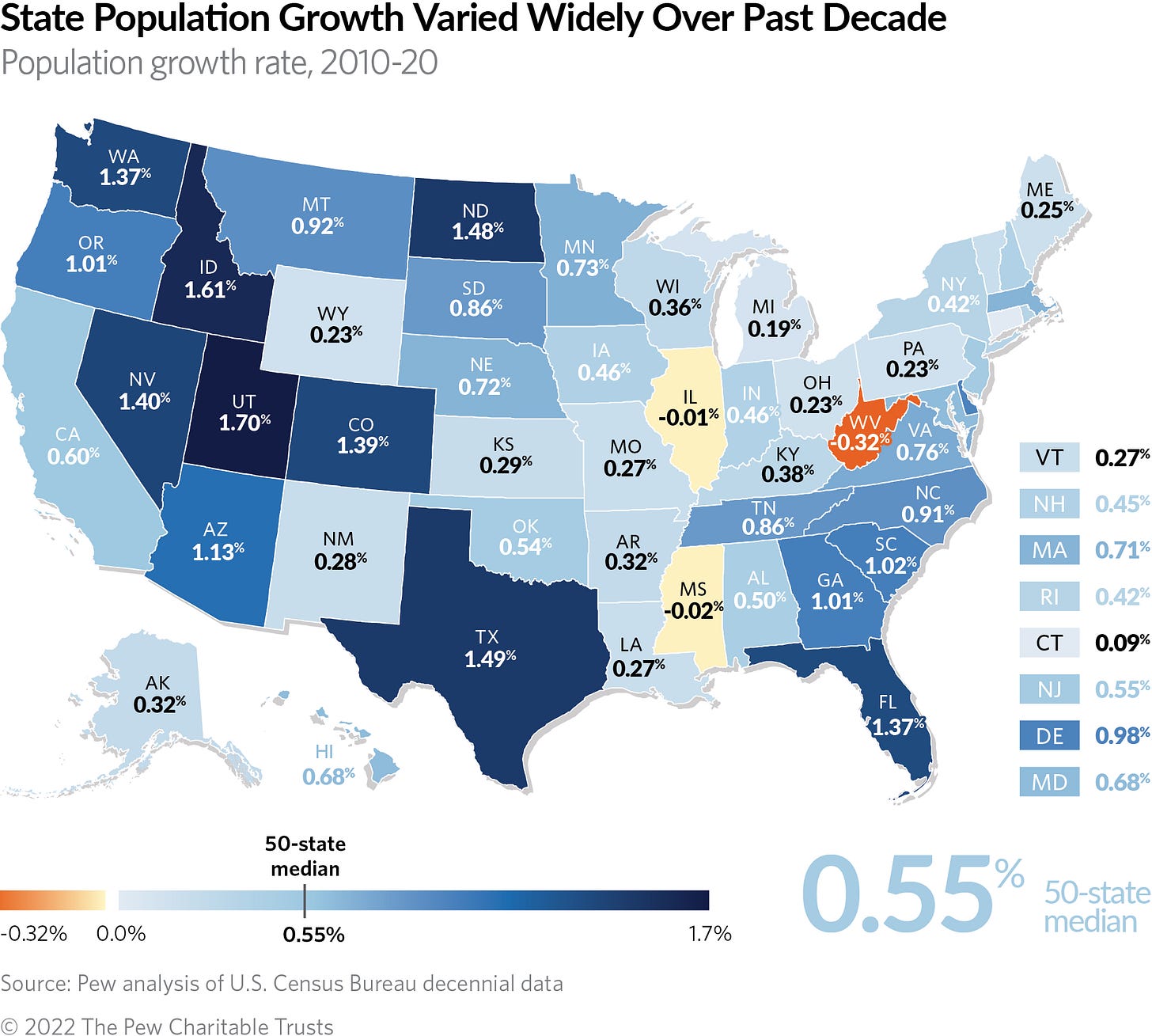

The crisis hit New Mexico especially hard, for reasons I’ll explain soon, and population growth slowed. Even as the rest of the West kept growing, a lack of opportunity kept the Land of Enchantment at a crawl.

While overall population growth was basically stagnant, within-state movement since shows people leaving rural areas, opting to live in cities, suburban areas, or the Permian Basin in Southeastern NM - which is the most productive oil and gas basin in the highest-producing country in the world.

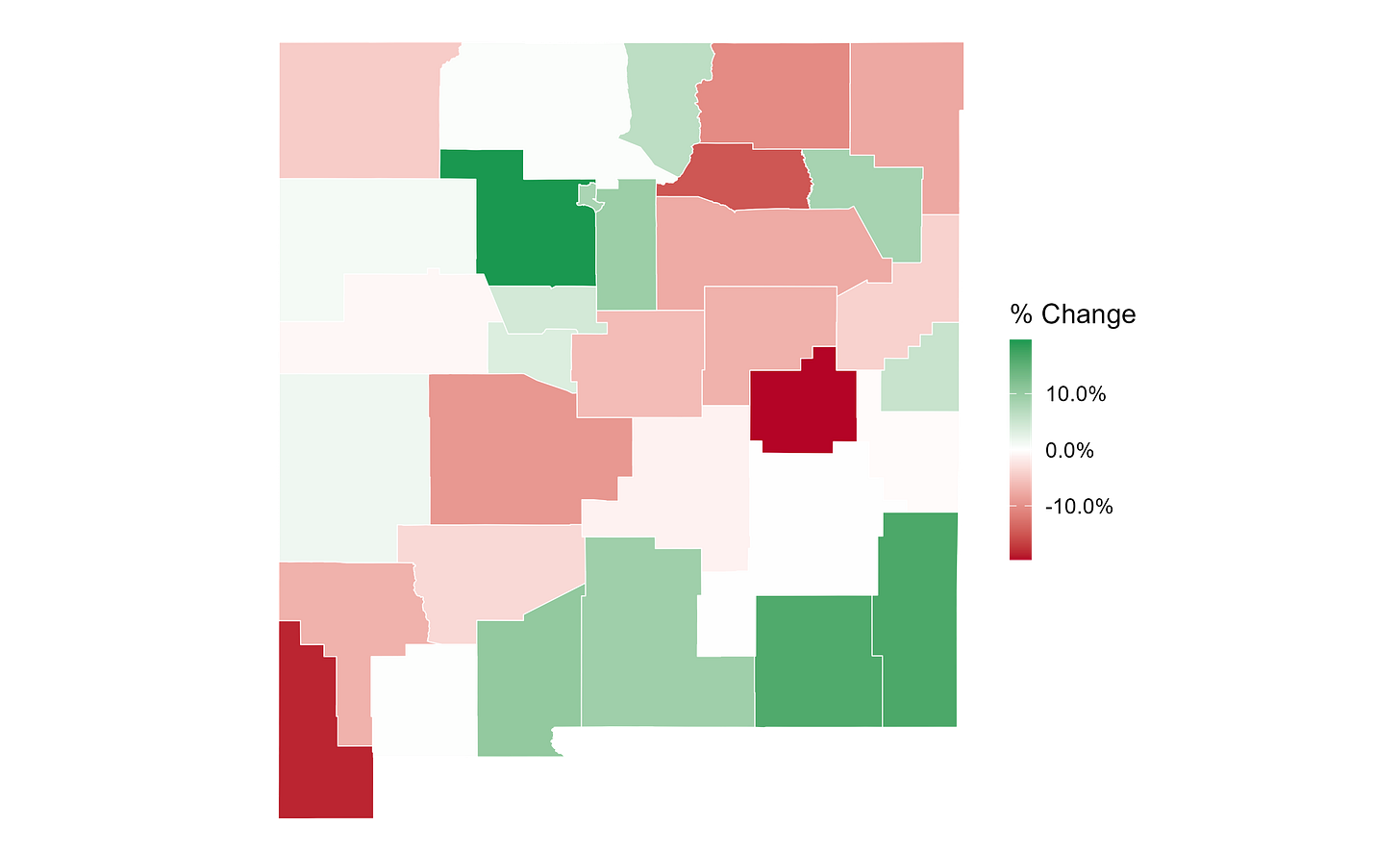

NM County Population Change 2008-2023

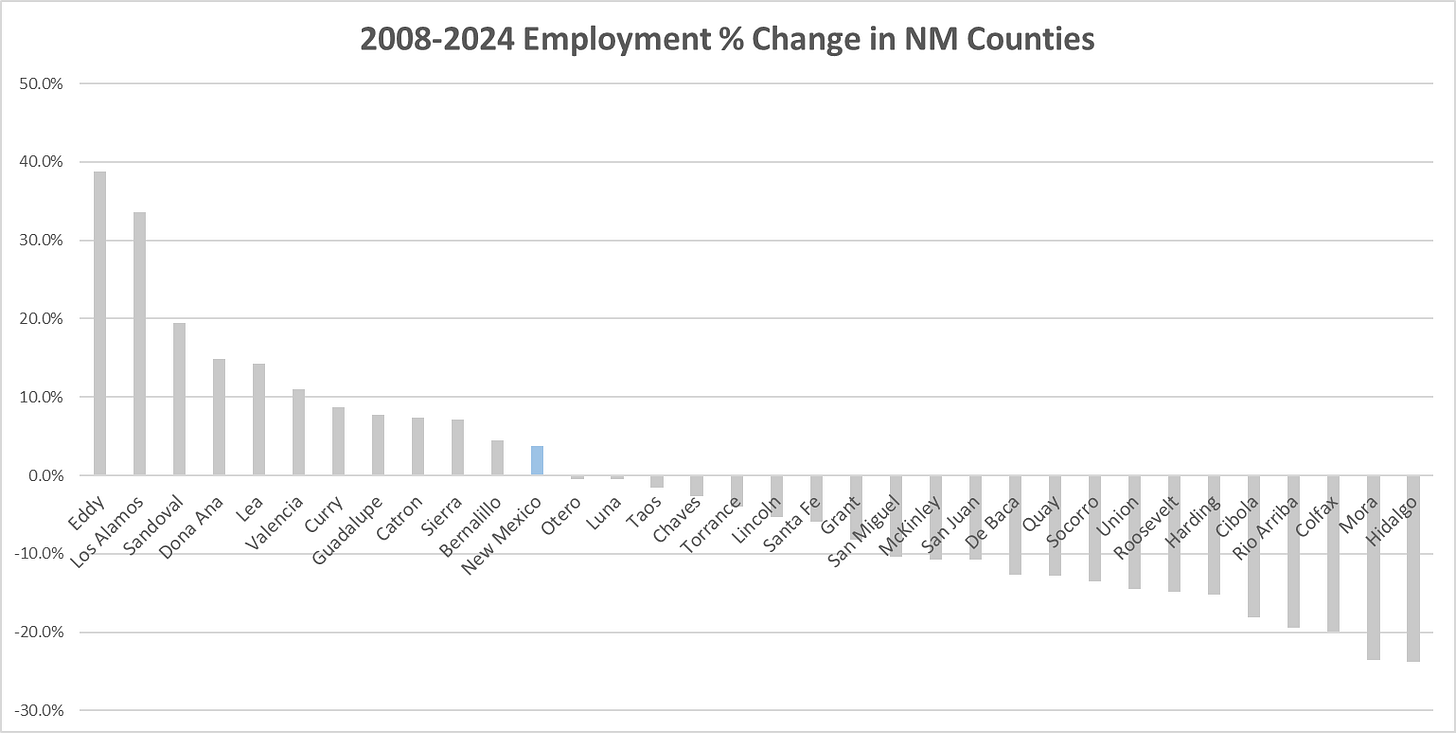

Changes in employment from 2008 to 2024 mirror, and perhaps explain, these within-state migration trends. Eddy and Lea counties, home of the New Mexican side of the Permian Basin, are two of the 11 counties that have seen positive employment growth since the GFC.

There are many theories on why the financial crisis kicked off the lost decade in New Mexico, but the most believable theory goes something like this. Once the recession hit, large companies consolidated their workforce to larger urban clusters outside of the state. Intel, a company that in 2009 supposedly made up over 10% of New Mexico’s manufacturing employment, shed nearly half of its workforce in the state. Other top employers like Caterpillar completely left. Home-grown companies also tightened their belts with lay-offs. Anecdotally, it was during this time that my dad was laid off from the hotel he managed. There were ripple effects throughout the economy, and employment didn’t recover until roughly 2019, which is why I think this is about when the lost-decade ended.

One could argue that the lost decade lasted through the Covid pandemic, but recovery from that was a bit quicker thanks to government stimulus and a New Mexican economy that was more resilient than it was in the decade prior.

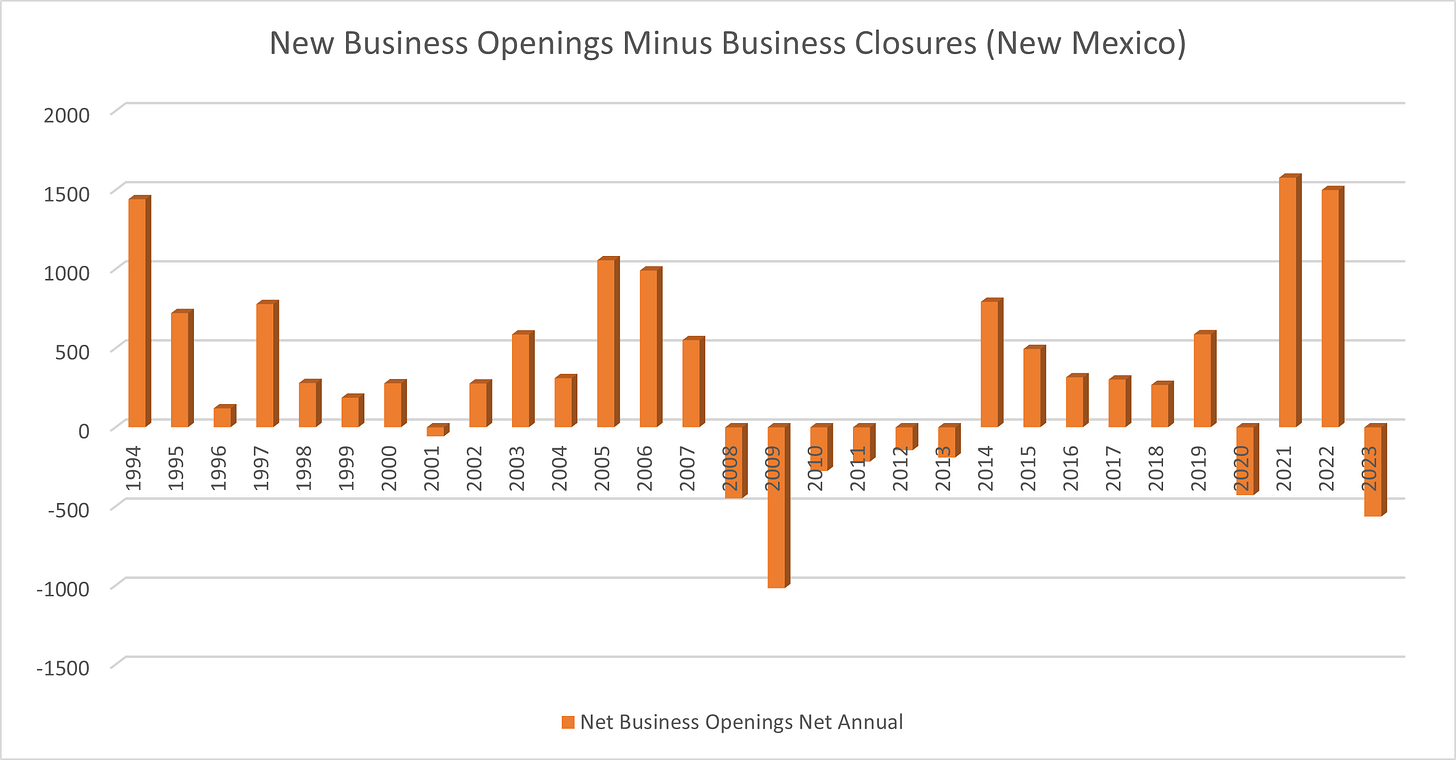

Economic development and entrepreneurship also lagged during the lost decade. There were at least 6 years of entrepreneurial decline following the housing bubble crash, which has since bounced back.

As the story goes, New Mexico’s response to the financial crisis was subpar. While other states expanded their economic development incentive programs following the GFC, New Mexico did the opposite and cut down or eliminated their most successful incentives. The economic development world is highly competitive, and attracting large employers takes big incentives, an educated workforce, infrastructure-ready building sites, healthy venture capital ecosystems, etc. - and New Mexico couldn’t compete for jobs as the rest of the nation recovered from the recession.

Of course, there is likely more to the story. New Mexico’s lost decade can’t completely be explained by a few companies leaving and a poor government response. I’m sure other factors were at play - like deeply-engrained poverty, poor education, a general unawareness of New Mexico compared to the rest of the West, etc. - but it’s a decent explanation.

The Divergence

As New Mexico saw rural populations decline, similar to the rest of the nation, the economic landscape started to shift as well. Many unemployed people and new graduates started leaving the state, as depicted above, but those still here had to figure out what to do for work. My dad, for example, managed a hotel in California for a while after being laid off from his local job. Others found work in the oil fields, government, the national labs, etc.

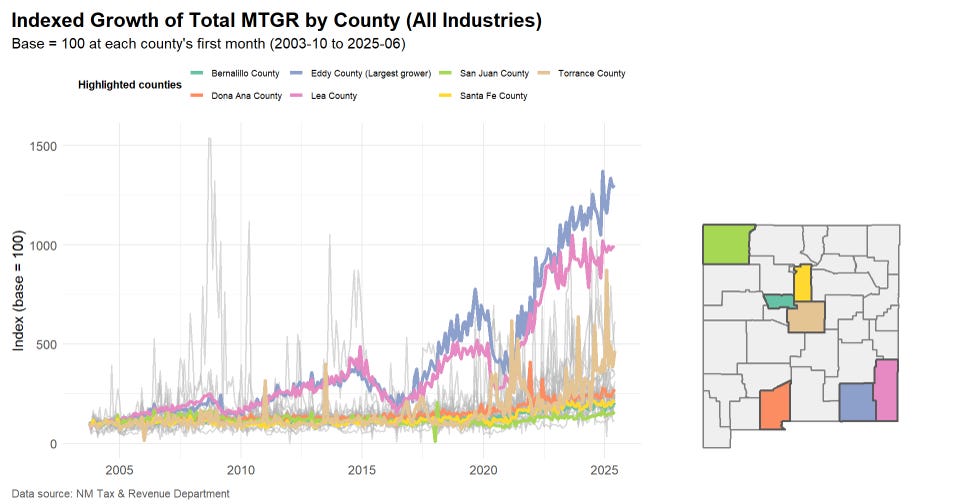

Gross receipts data collected by the NM Tax and Revenue Department help tell the economic story since the recession hit. Matched Taxable Gross Receipts (MTGR), basically the total amount of money businesses report from taxable sales of goods and services, are reported at the county level. This economic activity shows which industries were likely hiring during the lost decade.

I indexed this data to show relative growth over time by county. The following graph illustrates the dip in economic activity the state experienced during the recession, then it shows the Permian basin counties start to separate themselves in terms of growth.

From 2008 to 2019, most of the counties’ MTGR saw only mild growth, outside of the Permian and some metro areas. The divergence between the Permian basin and the rest of the state becomes quite stark over the lost decade, where it seems like we have two very different economies. In absolute terms you can see the insane growth of Lea and Eddy counties in the following video, especially in the past couple years.

There are a plenty of story lines to follow above, so I’ll highlight a few. First, it’s quite obvious how dominant Albuquerque and Bernalillo County have been economically for the state. This isn’t too surprising given 1/3rd of the state’s population lives in Bernalillo County. The big county’s largest industry over the past few decades has been retail trade, making up 23% of activity today. The fastest growing industry over the past five years has been arts, entertainment, and recreation.

The next storyline I’ll point out is San Juan County’s. Through the 2000s, San Juan was the second-most active economic hub in the state, with the largest industry being oil and gas extraction. Since the recession, San Juan County’s largest industry has been retail trade. Depleting oil and gas resources, aging wells, and a shift in the economics favoring shale plays (like the Permian) tell part of the story of San Juan’s decline. Over the last five years, the fastest growing industry has been public administration.

Eddy and Lea counties basically follow equivalent storylines to each other. Their meteoric rise to the number two and three spots among top MTGR counties is driven by oil and gas. Oil and gas make up 36% and 37% of Lea and Eddy counties MTGR, respectively, and that industry has unsurprisingly been the fastest growing, making up 58% and 59% of growth in the last five years. These two counties combined are 1/5th the population of Bernalillo County, but have surpassed Bernalillo in MTGR.

Turning a new leaf

I think many people would disagree with me when I say the lost decade is over, but that’s only fair. There’s still a lingering feeling that New Mexico will be stuck in stagnation. But since Covid, there are actually plenty of counties that are starting to grow. Torrance County is making a comeback with large growth in the construction industry recently. Dona Ana, Otero, Sandoval, Curry, and Valencia Counties are also seeing consistent growth, and the State government is richer than it’s ever been. New Mexico has had the fastest growing household income since 2020 out of all states, and also has the been gaining manufacturing jobs quicker than most states.

The Governor may tell you that her policies have helped turn a new leaf in the state - and she may be right. New Mexico has been attracting manufacturing and tech jobs again, and state and local politicians have certainly helped make that happen. And there’s no question that oil and gas has helped fund it.

While the lost decade has ended, we still need to reconcile with the awkward divergence between the Permian counties and the rest of the state that evolved over the lost decade. New Mexico is a majority blue, liberal, state that believes climate change needs to be reckoned with, but the climate-changing fossil fuel industry has filled state coffers in recent years giving us exciting opportunities - such as funding free college and universal childcare.

On one hand, we’ve got an industry that could help fund our comeback story, and on the other we have a desire to live in a mild-weathered, beautiful state saved from pollution and climate change. For New Mexico to continue to be a habitable and comfortable place to live, some of that oil is going to have to stay in the ground.

In my next post I’ll write about the New Mexico government’s increased dependence on the oil and gas industry, and the unprecedented wealth the state is hoarding in our Sovereign Wealth Fund. New Mexico may never lose its scars from the lost decade, but I’d say there’s good reason to have hope.

Thanks for this insight.