Climate action in the age of Trump

Blue states will need to focus on politically-feasible climate policy. Some studies give hints as to what feasible policies look like.

A second Trump term doesn’t bode well for the urbanist, progressive, or climate policies I’ve discussed on this blog. Now that the GOP controls the White House, the Senate, and possibly the House of Reps, we should only expect climate policy regression at the Federal level - at least for the next couple of years. Trump has talked about dismantling the EPA, reversing the Inflation Reduction Act, cutting spending for public transportation, and ‘unleashing big oil’, and I’m sure he’ll accomplish much of that. But I don’t want to dwell on that today. I’ve always tried to keep this blog optimistic, and there’s still work to be done - particularly at the state and local levels.

A second Trump presidency means blue states and cities need to become strongholds for climate action. That doesn’t necessarily mean local Democratic politicians need to pass the most aggressive climate policies there are - I mean, that would be nice - but it means Democrats should start looking to the policies that actually have a chance of passing.

When contemplating climate policies, policymakers should consider the policy’s overall efficiency. Four quadrants of efficiency should be considered: Cost Efficiency, Effectiveness, Feasibility, and Fairness. My professor, Mar Reguant, and her colleague, Natalia Fabra, in their paper The energy transition: a balancing act (2023) argue that it is not enough for a policy to simply be cost-effective if the resulting efficiency only benefits the rich; and it is not enough for the policy to be effective if there isn't a politician willing to attach their name to it.

On this backswing in the political pendulum, the top right quadrant in the efficiency chart below becomes more important than ever.

Objectively, a carbon tax set at a level equal to the social cost of carbon ($190) would be the most cost-efficient way to decrease greenhouse gas emissions economy-wide, but it is wildly unpopular in the United States. The political left doesn’t like that it’s regressive at face value (even though you can return the proceeds in the form of a rebate and make it progressive) and some think it’s perverse to “sell the right to pollute.” The political right doesn’t like a carbon tax for obvious reasons. Proposing any tax is political suicide in the US these days.

Furthermore, a carbon tax at the state level, while efficient, may promote carbon and economic leakage - meaning firms would simply choose to emit carbon and do business in (leak into) a neighboring state. Because of leakage, a carbon tax would make the most sense nationally or internationally. And that’s not going to happen anytime soon. Therefore, until a carbon tax becomes more popular nationally, we need to look elsewhere for emissions reductions.

States with Democratic Governors may be able to pass electric vehicle mandates, like Advanced Clean Cars, via rulemaking procedures. States with majority Democratic legislatures may be able to pass more politically resilient policies like the Low Carbon Fuel Standards.

When thinking about decarbonizing the transportation industry, the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) - or the Clean Transportation Fuel Standard (CTFS) as it’s known in New Mexico - is cost-efficient, effective, fair, and much more popular than a carbon tax. It’s not a perfect policy, but it decreases emissions and is politically feasible for blue states. Some claim it has negative land-use implications due to ethanol production, but perfect can’t be the enemy of good. Let’s take what climate policy we can get. Feasible state-level climate policies will survive a Trump Presidency and allow parts of the US to make progress in a warming world.

I’ll illustrate the importance of finding politically feasible climate policies using the Low Carbon Fuel Standard as an example.

What is the Low Carbon Fuel Standard?

In brief, the Low Carbon Fuel Standard is a market-based policy aimed at decreasing the carbon intensity (CI) of the transportation fuels available to consumers. It is fuel agnostic, meaning it applies to all transportation fuels, such as electricity, gasoline, diesel, hydrogen, biofuels, etc. The state sets a carbon intensity standard that decreases over time - in most cases, by 20% by 2030. Some states like New Mexico are more stringent and will further require a decrease of 30% by 2040.

Looking at the graph above, the CTFS becomes quite intuitive. If you are a producer producing transportation fuels with a carbon intensity below the dotted line, you will generate credits and sell them to producers producing fuels above the carbon intensity line. As the CI standard decreases over time, the mix of transportation fuels will have a lower and lower carbon intensity, and the transportation industry therefore emits less carbon into the atmosphere.

For more basics on the CTFS, you can look at the NM Environment Department’s Climate Change Bureau site or California’s Air Resources Board site.

Support for the LCFS

Support for the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) was studied in a few different papers we will glance through now briefly.

Rhodes et al. note, “Numerous studies have shown that market-oriented regulations such as the LCFS are more widely supported by the public than carbon pricing policies” (2014, 2015). This is one of the most significant findings. This means that framing climate action in the context of the “free market,” where you’re not explicitly taxing or banning high-carbon fuels, and instead encouraging competition, makes the climate action more popular.

To some on the far left, this is a bad thing. As I wrote in this piece:

In a nutshell, the far left thinks anything that slightly resembles capitalism is a bad thing. I argue that there isn’t time to “dismantle” capitalism before we address climate change. Plus, according to the most recent election, the US is moving further right. Climate advocates need to be ok with meeting the rest of the country where they’re at. If a policy reduces emissions and centrist Democrats are willing to vote for it, it’s a policy worth considering.

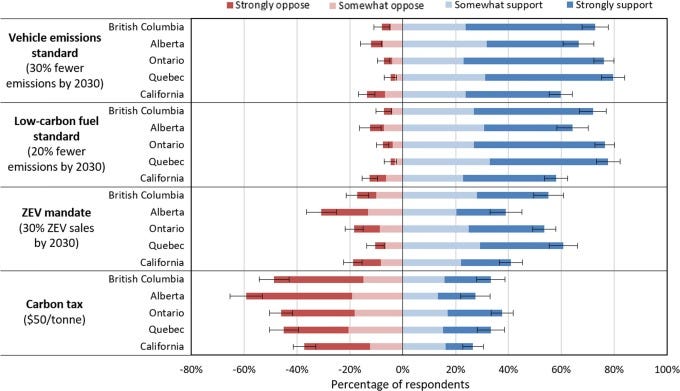

Another study shows that support in Canada and California is high for the LCFS at the current 20% CI reduction by 2030 framework. They also find support is lower for zero-emission vehicle mandates and much lower for carbon taxes:

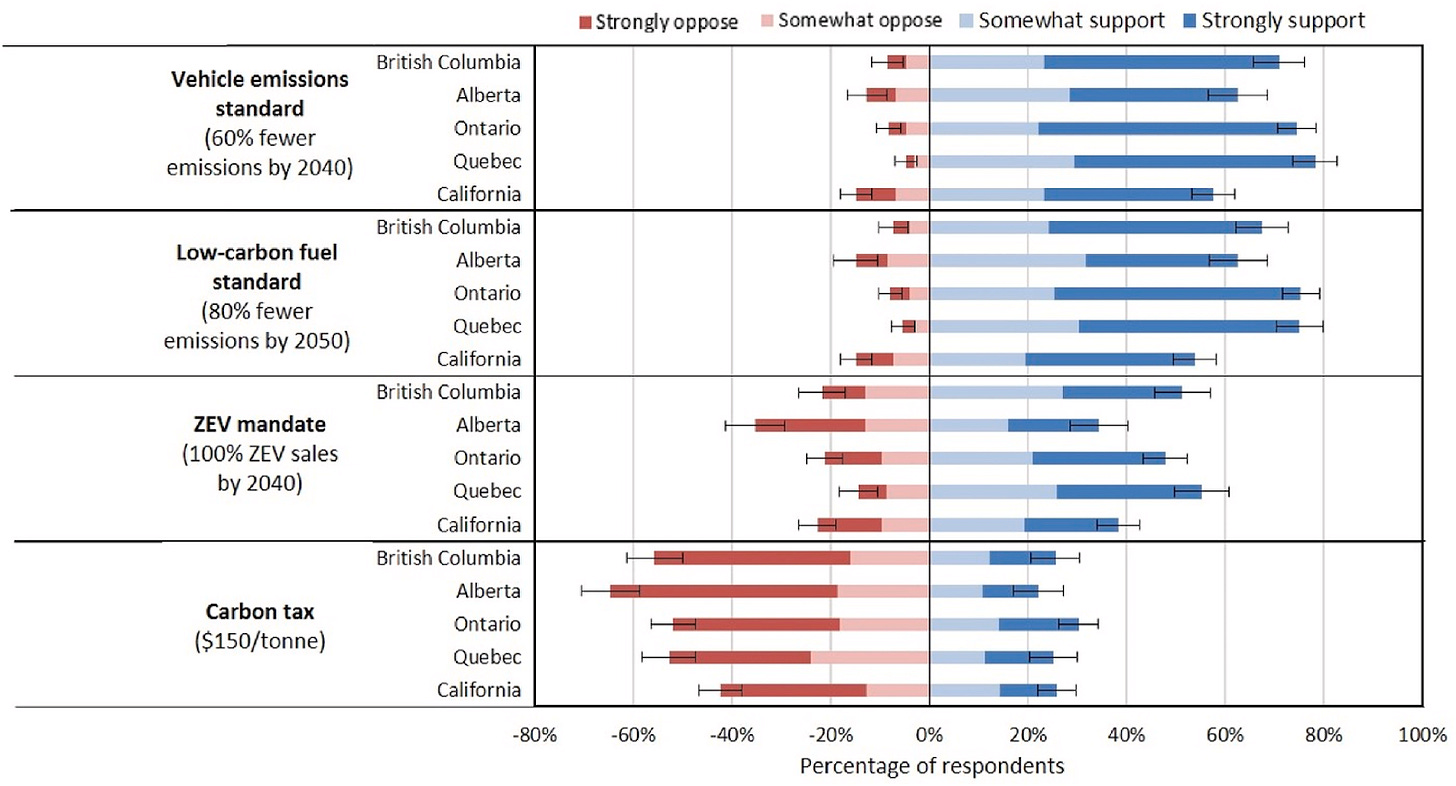

Interestingly, support for the LCFS remains high when the policy calls for an 80% CI reduction by 2050. In fact, support/opposition remains virtually unchanged across all the policies at much higher stringency levels:

This confirms that people are more willing to support market-based policies over taxes and mandates no matter the stringency.

The LCFS is as popular as vehicle emissions standards, more popular than ZEV mandates (like Advanced Clean Cars), and much more popular than a carbon tax. Therefore, the LCFS holds less political risk than a carbon tax or ZEV mandate - giving it the potential to enable greater emissions reductions than we are currently demanding from it.

The study finds that policies framed around industry requirements instead of individuals are more publicly supported. Even though both “would likely indirectly incur costs to consumers…, survey respondents may not have perceived this potential impact from each policy” (Long et al., 2020).

Now, if the Low Carbon Fuel Standard is so popular, why haven’t more states enacted one?

More US states have ZEV mandates than have a Low Carbon Fuel Standard despite Long’s suggestion that they are less popular. There are four states with an LCFS in the US and 12 states plus DC have ZEV mandates. This could be due to what I mentioned before: ZEV mandates can typically be passed without legislative action - and instead via rulemaking. Low Carbon Fuel Standards are seemingly always enacted with explicit support from a state legislature, which is objectively more difficult and politically resilient than rulemaking.

For example, under Governor Bill Richardson, New Mexico adopted fairly stringent ZEV mandates in the mid-2000s. This was via EIB rulemaking and not the legislature. Once Richardson left office, the ZEV mandate was left vulnerable to the Republican administration of Susanna Martinez - who did away with the mandate. A stricter ZEV mandate has since been enacted during the Lujan-Grisham administration.

ZEV mandates should be a key strategy to reduce emissions at the state level, but its political vulnerability should be noted. For this reason, I believe the Low Carbon Fuel Standard is more powerful and should be considered by more blue state legislatures given the popularity of the policy.

Climate change was essentially a non-issue during this Presidential election cycle. Either that’s one of the reasons Harris lost, or maybe it’s not as important to the average voter - I don’t know. I’m not a political analyst, but if the climate is ever going to be a major and sturdy part of the Democrat’s agenda, Democrats should identify the policies that aren’t just effective, fair, and cost-efficient, but politically feasible.

If you’re in a state with a Democratic Governor and a red or purple legislature, maybe a ZEV mandate is the best that can be done for now. If you’re in a state with a blue legislature, market-based climate policies may have the political backing necessary to pass.

There are dozens of climate policies available to states, and states like New Mexico, despite having an LCFS, have a long way to go to decarbonize. I don’t know what the next four years have in store for the US, but I know that climate action is now up to the states.

You probably know this, and I don't know what other climate policies were on the ballot in which states, but Washington state voted to keep its cap and trade policy! Were they bucking the trend?

Thanks again for focusing on what CAN be done about climate change, and for the good info about low carbon fuel standards.