New Mexico got rich. Now what?

Coming out of the lost decade, New Mexico's piggy bank is overflowing with $66B in oil and gas revenue. Beyond free college and childcare, the state is putting that money to work at home.

New Mexico was slow to recover from the 2008 financial crisis. A poor government response led to painful job losses and a stagnant population. And people left rural New Mexico in search of opportunities in cities and the Permian basin. Economists call this period after 2008 the ‘lost decade’. Then before the pandemic hit, the economy started to show life again. With the rise of the oil and gas industry, population growth inched upward again, economic growth returned, and fossil fuel revenues started pouring in. While many New Mexicans are still poor, in the 6 or 7 years since the lost decade ended, the State of New Mexico became very rich.

The oil and gas boom of the last few years is unlike anything the state has experienced before. It poses some serious threats, but also many opportunities for the state’s economy. The revenue brings with it the risk of dependence on a single boom and bust industry (that’s to blame for the changing climate). But on the other hand, the state’s growing piggy bank could help diversify the economy towards a more sustainable and fruitful future.

The piggy bank I’m referring to is New Mexico’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). The fund has historically invested its portfolio out of state, but as of recently, its investing billions of dollars in the local economy - aiming to boost target industries like quantum and advanced energy. The energy transition is playing a cornerstone role in transitioning the state economy away from oil and gas, but I’ll leave that topic for a later post. For now, I’ll focus on New Mexico’s rapidly growing Sovereign Wealth Fund and the new domestic investments that make it unique in the US.

The Oil and Gas Revenue Boom

Despite the high poverty numbers, New Mexico is a very rich state. The unprecedented rise in fossil fuel production in the Permian basin has, quite literally, led to more state revenues than we know what to do with.

60% of the growth in New Mexico’s economic activity (MTGR) since 2020 has come from oil and gas extraction. The state generates revenues from this extraction in multiple ways: gross receipts taxes (sales taxes), severance taxes, State Land Office leasing, Federal Mineral leasing, and personal income taxes. This revenue goes either directly into the state’s General Fund or into one of the Permanent Funds in the SWF.

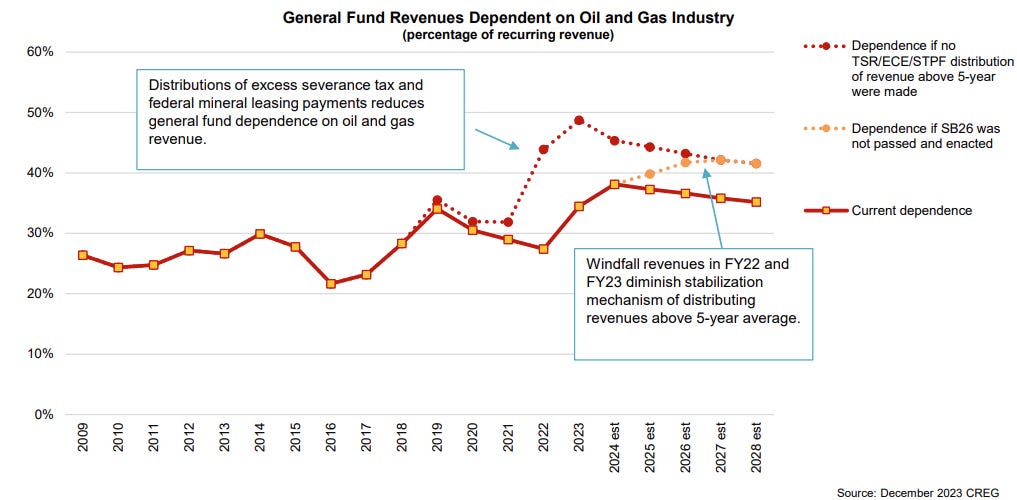

The state’s General Fund, the bucket of money that finances regular government operations, has become increasingly dependent on the oil and gas industry. Through taxes and leasing fees, the industry now provides nearly 40% of New Mexico’s general fund revenue. And when counting interest income from permanent funds, the dependence is closer to 50%.

To be fair, New Mexico isn’t as dependent on oil as Alaska, which regularly receives up to 90% of their general fund revenue from the oil industry. Nevertheless, that’s an unsustainable road New Mexico doesn’t want to go down.

Oil and gas has provided big revenues to the state, but it also poses climate and financial risks. Climate change may be less of a political issue today, but it’s threats still loom. Ideally, some of New Mexico’s oil and gas will stay in the ground. Even if every last drop of oil was extracted, New Mexico will have to figure out what to do next - Alaska’s oil boom of the 90’s eventually slowed down, and that’s certainly in New Mexico’s future as well.

The state legislature has been aware of these risks, and have therefore redirected more and more oil and gas revenues to permanent funds housed at the State Investment Council (SIC), otherwise known as New Mexico’s SWF.

What is a Sovereign Wealth Fund?

SWFs are basically investment accounts owned by a government. Typically they’re owned by countries or states that run a trade surplus - usually thanks to oil exports. These governments aim to capitalize on the trade surplus by saving money either for a rainy day or some other economic opportunity.

The largest, most well-known, SWFs in the world are in countries like Abu Dhabi, Singapore, Norway, China, and Saudi Arabia - each with funds in excess of a trillion dollars. All of these countries run a trade surplus, and many of them use their funds to, among other things, relieve tax burdens on their citizens, provide private investment efficiency, and stabilize foreign exchange earnings.

You’ll notice that the US is not in this list despite being regarded as the richest country on the planet - and that’s because the US doesn’t really need a SWF. The US doesn’t run a trade surplus, so how would a SWF be funded? The US has the most advanced private investment ecosystem in the world, and public grants and loans would make any new fund’s investments redundant. And dollar dominance means the Federal government can issue debt in its own currency. President Trump’s fixation on building an American SWF may have more to do with pageantry than economic reasoning.

On the other hand, it makes sense for governments like New Mexico and Alaska to have a SWF because they have a trade surplus, plenty of natural resources to export, a need to stabilize general fund revenue, and need a boosted private investment ecosystem.

New Mexico’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF)

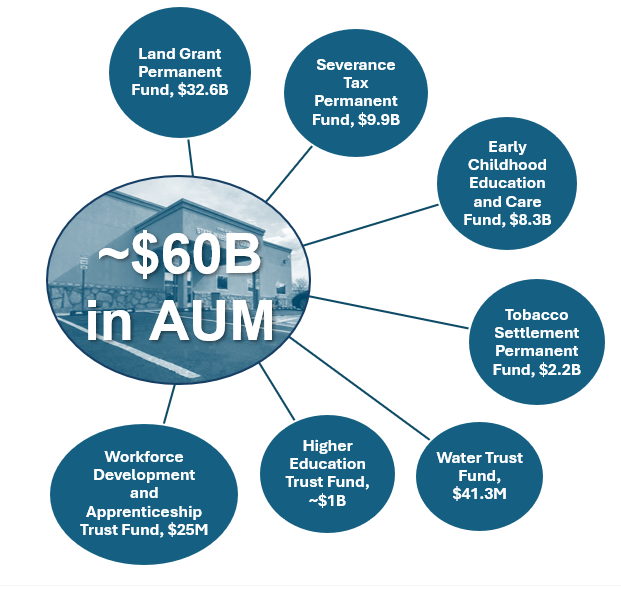

New Mexico’s SWF, wears many hats: it provides the General Fund with interest income, finances water infrastructure projects, invests in free childcare and college for all New Mexicans (the only state to do this BTW), and more.

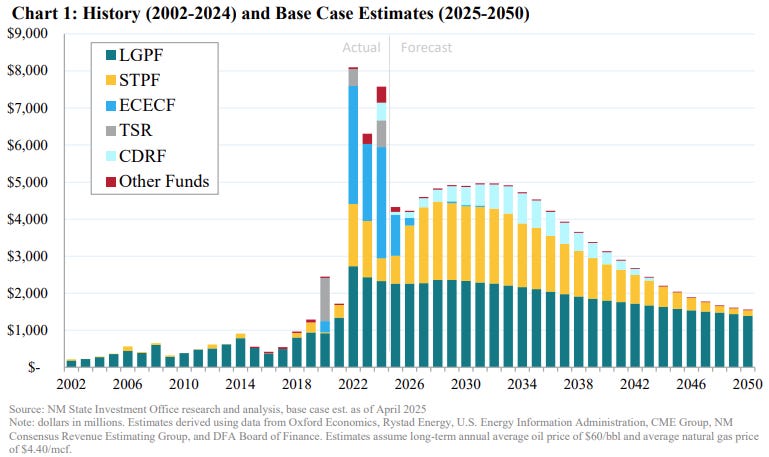

As of January 2025, New Mexico’s SWF had nearly $60B in assets under management - making it the second largest in the nation. Since the beginning of the year, the fund has already grown to nearly $66B. Analysts project that it will surpass Alaska’s SWF to become the largest in the nation by 2030 - reaching $100B or more. The incredible pace in which fossil fuel money is entering state coffers is highlighted by the fact that revenue is coming in faster than the SIC can invest it. Top 1000 Funds reported last year:

The SIC is expecting $5 billion in inflows this year following $8 billion in both 2023 and 2022, and is currently around 10 per cent overweight cash and bonds relative to target.

“We are seeing massive capital coming into our funds,” says [New Mexico SIC Chief Investment Officer] Smith in an interview... “our large cash allocation is due to the large inflows, not by strategic choice.”

As charted below, the SIC expects the boom to continue.

Rystad Energy analysts, and the Legislative Finance Committee (LFC), expect oil and gas production to peak in the 2030s. The SIC, as shown above, seems to project the same, though their forecast looks rather conservative based on current trends.

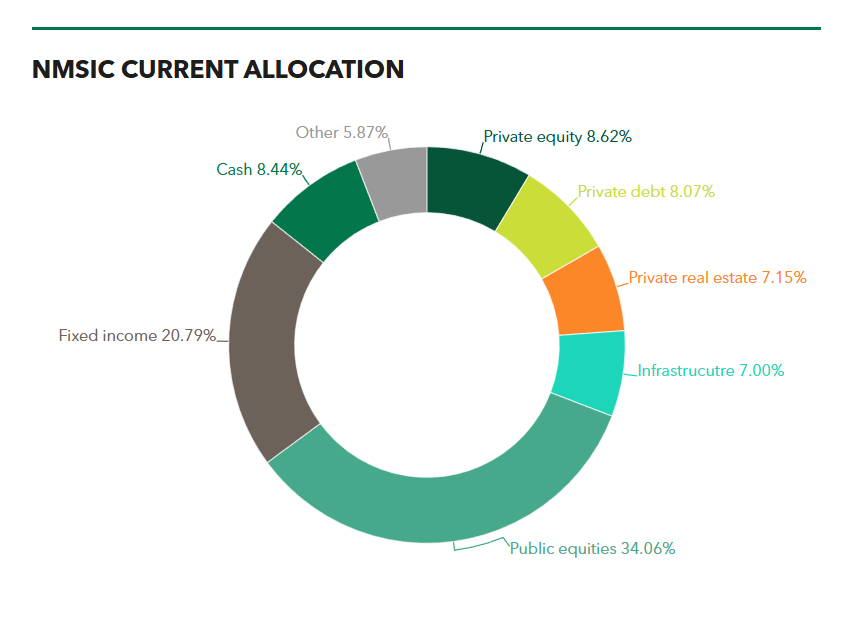

Investment decisions are made by a professional staff of analysts and the council-appointed State Investment Officer, while the policies and strategies are guided by the SIC’s 11 council commissioners: the Governor (who is always the Chair), State Treasurer, State Land Commissioner, DFA Secretary, a higher ed CFO, four public members appointed by the Legislative Council, and two public members appointed by the Governor. The SIC’s portfolio currently consists of 34% public equities, 20% fixed income, 8.6% private equity, 8% cash, and so on down the list of asset classes.

Many SWFs around the world, including New Mexico’s, historically, invest their dollars primarily outside their state or country. NM SIC doesn’t explicitly publish their share of assets that reside in New Mexico, but as of 2017, their accumulated New Mexican assets totaled about $319M since the creation of the SWF in the 1950s.

Recent changes to the way the SIC invests aims to increase local investments dramatically, with big local investments being made over the last year and a half. As Buyouts Insider writes:

…that [in-state private equity] platform, which is meant to help bolster New Mexico’s economy, is being reshaped with some changes to which funds qualify for that program and more of an emphasis on venture capital…

New Mexico Economic Development Secretary talks about this turning point quite a bit. On the Bob Clarke podcast a few days ago he noted:

[The SIC has] taken about two billion dollars, a billion in the the last four months, and moved it into funds that are the best, highest performing deep tech venture funds in the world… things around advanced computing, advanced energy, space, defense, all areas that align with our economic development strategy, things that New Mexico has a right to win because of the history and our workforce, our research labs, and our research universities.

An additional $2B of local investment marks a stark difference to the $319M total local portfolio in 2017. Other large SWFs around the world deploy their capital in similar ways. Saudi Arabia and UAE grew rapidly in part due to their domestic SWF investment strategies. New Mexico is now the only US state using their SWF to spur local growth in this sort of aggressive manner.

During the Governor’s Economic Development Conference last month, many out-of-state site selectors pinpointed the drivers that entrepreneurs consider when coming to New Mexico. They look for competitive incentives, good infrastructure, sites ready to build on, a compatible workforce, and a healthy VC ecosystem. I argue New Mexico has all of these attributes but the VC ecosystem, which is obviously changing.

A healthy VC ecosystem is important for providing access to capital and follow-on funding for startups, signaling investor confidence, attracting and retaining talent, fostering innovation spillovers, and complementing public incentives - which is why this recent change in the SWFs investing strategy could be a turning point.

Is it going to work?

While it’s still early days, NM Angels reports that we’ve already seen some positive results including high growth in startup capital investment and venture deals. Just last month the SIC committed $25M to a quantum venture studio in downtown Albuquerque, complementing the local tech workforce and training programs. Pacific Fusion, a leading nuclear fusion company, announced a $1B facility in Albuquerque, also partly backed by SIC partner funds.

Population growth remains the clearest indicator of whether new state policies are translating into real economic opportunity. Demographic and economic trends move together - when economic opportunities arise, people show up or stay put. Without opportunities, people leave. Population stagnation during the lost decade gave way to slow growth over the last few years, but can the state match growth rates seen in Arizona, Colorado, or Texas? If the SIC can help differentiate New Mexico as a great place to live and work, I don’t see why not.

I’d like to see investment in transportation infrastructure - perhaps an expansion of the Rail Runner - along with affordable housing, which is often cited as another top factor holding Albuquerque’s economic development back. The SIC could also explore partnerships with utilities to accelerate grid-scale battery deployment or geothermal assets. There are plenty of projects that would offer the returns the SIC is mandated to pursue while building an economy New Mexicans, and others, want to be a part of.

The lost decade scarred many New Mexicans. We’ve been hearing that New Mexico has ‘potential’ for so long that it’s become a curse word. It’s felt like no matter what we do, we’re always on the wrong end of the rankings - last in education and first in poverty. But one positive ranking is that New Mexico will soon have the number one largest wealth fund in the nation. ‘Potential’ isn’t a curse word when it’s paired with the right opportunity. New Mexico is rich now, which feels like an opportunity to me.

Maybe we should build some state funded housing and open a few state funded hospitals?

Fantastic! I am excited for New Mexico’s future. Very informative and a wonderful read.